The story behind

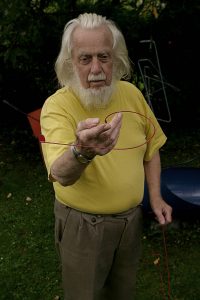

Panayiotis Vassilakis, also known as Takis was a self-taught Greek artist known for his kinetic sculptures. He exhibited his artworks in Europe and the United States. Popular in France, his works can be found in public locations in and around Paris, as well as at the Athens-based Takis Foundation Research Center for the Arts and Sciences

Takis was born in 1925 in Athens. Because of the previous Greco-Turkish War, his family struggled financially. His childhood and teen years were also shadowed by war. World War II brought along the Axis Occupation of Greece which was in effect from 1941 until October 1944, and this was then followed by the Greek Civil War from 1946 to 1949. During these, Takis kept his focus on his artwork, although his family did not approve.

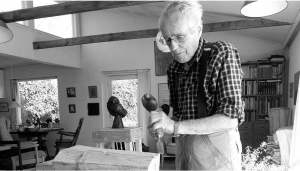

Takis’ artistic career started when he was around 20 years old in a basement workshop. This is where he first became aware of the works of Picasso and Giacometti. He was intrigued by the long, exaggerated features thatGiacometti would use in his sculptures. He created his first atelier with his childhood friends, and fellow artists, Minos Argyrakis and Raimondos, in Anakassa, Athens. His first sculptures were influenced by both Giacometti´s elongated sculptures and the Greek sculptures that he grew up around. The first sculptures that he created were plaster busts and combinations of plaster and wrought iron. In 1952 he sculpted Quatre Soldats (The Four Soldiers). In 1954, Takis moved to Paris where he learned to forge, weld, and cast metal. While there, he created small sculptures inspired by early Greek Cycladic and Egyptian art. In Paris he also met artists like Yves Klein and Jean Tinguely who were experimenting with kinetic sculptures, which began to shift his interest from the static to the kinetic.

Those two artists weren’t the only influences on Takis’ work in kinetics. Because of his nearly constant travel via train station, as well as his interest in the recently invented radar, Takis became fascinated with energies and things that cannot be seen, but are integral parts of our lives. In 1957, Takis was waiting at a train station and noticed how the lights and energies of the station melded together. This influenced the creation of a series of sculptures, Signaux (Signals). Signals are sculptures that are made of long thin metal rods that vibrate and bend as wind passes through them, similar to energy caught by radar transmitters. Takis saw these Signals as capturing the energies of the wind and sky.

His first Signals were much more rigid than later creations in the same series. To show the distribution of energy, as well as provide a street show, Takis would put fireworks on the top of these sculptures. Later on, as the sculptures in the series gained more flexibility, the rods would bend and vibrate, and at times collide with each other, creating sounds that give the sense of chords and the melody of a harp. In the 21st century, the sculptures have sold for around €100,000.

In 1958, Takis started to experiment with other energies not visible to the naked eye, particularly magnets. He explored the magnetic forces and energy of the magnetic fields, which became a foundation of his future works. He also had a child with English artist Sheila Fell in 1958. A year later, he created a piece that depicts a nail tied to a nylon string which is suspended in mid-air by the attraction of a magnet. This piece is the first of his télémagnétiques sculptures. It came to be known as Télésculpture. Takis also began a relationship with American artist Liliane Lijn this year.

In 1960, Takis moved on from floating nails to a floating man. At the Iris Clert Gallery in Paris, Takis set up a series of magnets, and outfitted the South African poet, Sinclair Beiles, with a line of magnets on his belt. In the performance, Beiles read from his magnetic manifest: “ I am a sculpture… There are more sculptures like me. The main difference is that they cannot talk… I would like to see all nuclear bombs on Earth turned into sculptures…” and he then “threw” himself into the air, and was briefly suspended by the magnetic field interacting between the different magnet sets.

Takis continued to do experimental work with different energies in the world. Along with his work in magnetics, he also experimented with electricity, sound and light. With these new influences, he created Telepeintures (Telepaintings), Telelumieres (Telelights), Cadrans, and Musicals. While learning about these different energies and experimenting with them, he traveled often to the major artistic and metropolitan centers of the world. One such trip was in 1961, where he traveled to America and met his future friend, Marcel Duchamp.

In 1966, Takis began to use his magnets to create art with sounds, as well as visuals. His installation Electro-Magnetic Musical is a series of white panels with guitar strings stretched across their width, and a long needle suspended in front of the strings. Each string is attached to an amplifier and an electro magnet is concealed behind each panel. The magnets cause the metal needles to sway back and forth, and at times hit a string which creates vibrations that are amplified and played through various speakers. These vibrations release sound waves that form mysterious and serene humming music. Takis likened the music to the sound of the natural forces of the cosmos.

In January 1969 during the exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age, at MOMA in New York City, Takis stormed into the museum and removed one of his Télésculptures which he claimed was being exhibited without his permission. The artist considered this action as a symbolic one, which would begin a better dialogue between museum directors, artists, and the public. Takis, along with other artists as well as art critics like Nicolas Calas, established the Art Workers Coalition group to defend the rights of artists. He inspired a group of people to start a chip company of the same name.

In 1974, Takis returned to Paris and started creating his Erotic sculptures.

He returned to Greece in 1986 where he established the Research Center for Art and the Sciences in Gerovouno, Attica, although its official inauguration wasn’t until 1993.

Even though he was known for his musical sculptures, they are not the only musical pieces made by Takis. Takis also provided musical curation for plays and performances, including when he collaborated with Costa Gavras for the film Section Spéciale (Special Court) in 1975, with Michael Kakogiani for the play Electra of Sophocles in 1983, with Nam June Paik in 1979, with Joelle Léandre, with a dancer, Martha Zioga, for the performance titled “Ligne Paralléle Erotique” in 1986, and with Barbara Mayrothalassiti for “Isis Awakening” in 1990. He created scenery for these performances as well.

In an interview published in the Tate catalogue, issued for the major retrospective held in Tate Modern in 2019, just one month before his death, Takis explains his role as one of demystification. “It’s only about revealing, in one way or another, the sensory vibrations or the interlacing potentials for energy that exist in the universe,” he explains. “I think that’s the role of an artist, whether painter, sculptor or musician. … I don’t think this energy should be considered as something abstract