The story behind

Niels August Theodor Kaj Gottlob, usually known as Kaj Gottlob, (1887–1976) was a Danish architect who contributed much to Neoclassicism and Functionalism both as professor of the School of Architects at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and as a royal building inspector.

After qualifying from Borgerdyd School in 1905, Gottlob attended the Technical School (1905-1908) and the Royal Academy, graduating as an architect in 1914. At the time, he was one of the young neoclassicists who used to meet at the Free Architecture Society (Den fri Architektforening). He taught at the Technical School (1915–17) and was an assistant at the Royal Academy’s Building School (1917–24). Between 1912 and 1923, he travelled to Greece, London, North Africa, Italy, Paris and Vienna.

After first working as an assistant at the Academy’s School of Architecture in 1917, he was appointed professor in 1924. In 1936, he succeeded Kristoffer Varming as royal building inspector and, in 1938, gave up his post as professor at the Academy.

As a young man, Gottlob showed interest in classical architecture, influenced in part by the English Arts and Crafts movement. Works in the 1920s include a residence at 45 Dalgas Boulevard (1924) and St Luke’s Church in Århus (1926). But like his peers, he soon turned to Nordic Neoclassicism, appreciating its sober, contemporary style. This can be seen in his Danish Student Hostel in Paris, completed in 1929. Though it was hardly international modernism, it was something of a breakthrough for Scandinavia. In designing Ørstedhus in 1934, Gottlob maintained some of the classical ideals, especially with the symmetry and hierarchical form of the facade. Standing on the corner of Gyldenløvsgade and Vester Farimagsgade in Copenhagen, the building was constructed by the cement firm Christiani & Nielsen. It is therefore not surprising that it was made of concrete and that, unusually for an office building, the facade remained uncovered. The windows were mounted in finely shaped frames and the pillars at the main entrance were lined with stainless steel.

Gottlob’s designs for a series of Copenhagen schools represented a break with classicism. In Katrinedal School (1935), the large central hall or aula served as an example for many Danish schools in subsequent years. Svagbørnsskole (1937), constructed in conjunction with Skolen ved Sundet, has south-facing fully glazed windows, opening onto the school yard. Both schools have aulas, symbolising modernism’s concern for light, air, health and nature. Gottlob’s largest project was for the university buildings at Nørrefælled. The additions, which include the school of dentistry and the zoological museum, were completed in stages in the 1940s and the 1950s. The area was conceived as an open park development where the trees played an important role. Gottlob’s relatively low buildings, clad in light travertine, respected the approach but later additions led to crowding.

As the architect responsible for the renewal of the two old bridges over Copenhagen’s harbour, he demonstrated his ability to combine attractive design with components created by engineers. Knippelsbro and Langebro, which play such an important part in the city, are among the finest examples of 1930s modernism in Denmark.

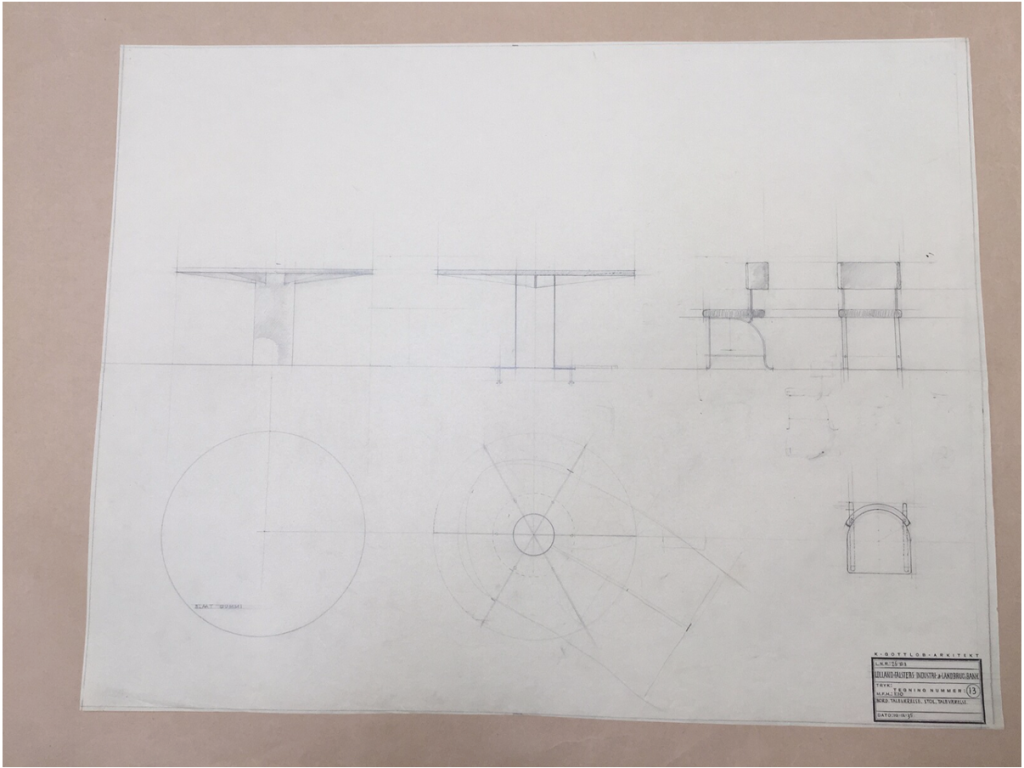

Other meaningful contributions by Gottlob in the 1930s were the furniture and fittings for the houses he designed. He also designed furniture for the Danish pavilion at the 1925 World Exhibition in Paris which was successfully exhibited by the cabinetmaker A. J. Iversen with whom he worked for a number of years. His furniture in an increasingly modern style could often be seen in the exhibitions at the Design Museum. An early example of his furniture is the Klismos Chair (1922), produced by Fritz Hansen in ash.